Research Areas

New Research

Tax Compliance

Covid Policy

Income Inequality

Tax Progressivity

Income Mobility

Tax Credits/Policy

Health/Pensions

Curriculum Vitae

Google Scholar

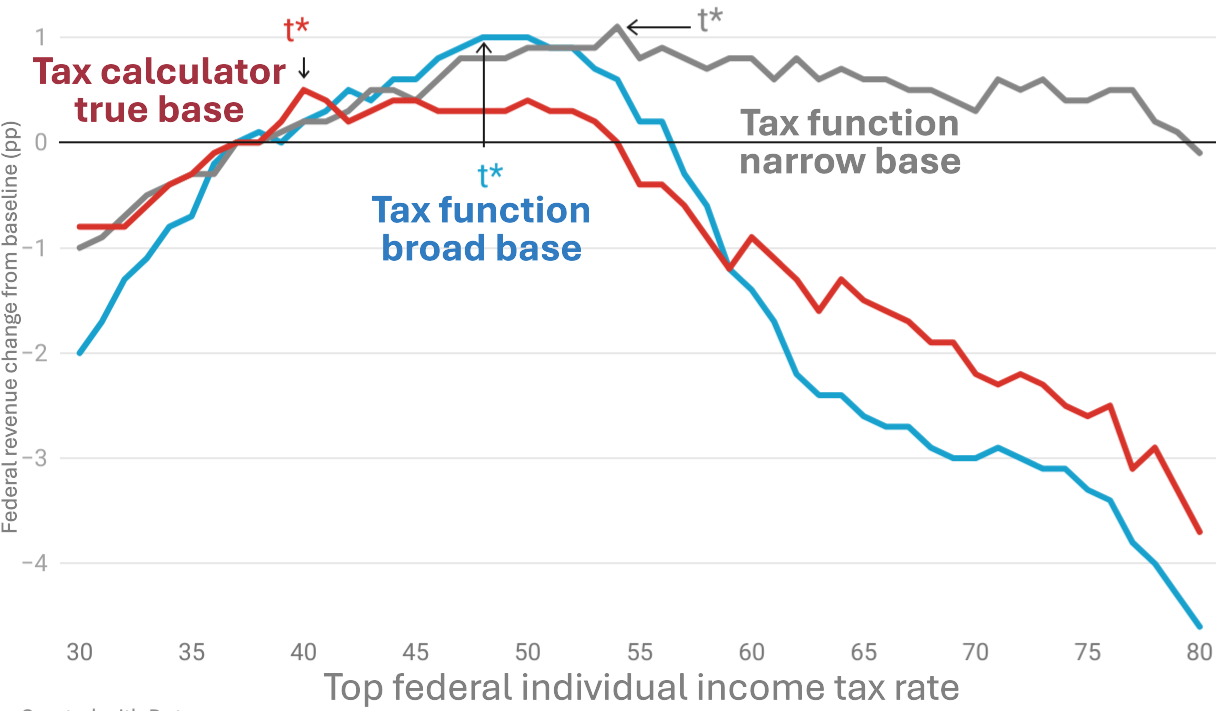

A public finance debate focuses on the "peak" of the Laffer curve — the point at which raising tax rates on the rich stops

increasing tax revenue and starts decreasing it.

Realistic Modeling of Taxes Matters

Most macroeconomic models of the tax system use "simplified" tax functions. These functions are elegant but deviate from actual

policy and use incorrect tax bases:

Modest Federal Tax Gains

Using 2022 as a baseline, we estimate a revenue-maximizing top statutory rate for federal taxes of roughly 40%. But increasing the top rate from its current 37% to the Laffer curve's peak rate only raises total revenue by about 0.1% of GDP. This is a small fraction of the current deficit.

The Laffer curve is flatter with the true tax base

Progressivity vs. Growth: The Real Tradeoff

If raising the top tax rates doesn't raise much money, what does it do? We argue for putting less focus on the "revenue-maximizing rate" and instead on the tradeoff between tax progressivity and growth.

Policy Implications

The policy takeaway is that the U.S. is already near the "flat" part of the Laffer curve.

References

Laffer Curves Are Flat (summary)

January 2026 (full paper, pdf)

Simplified "sufficient-statistic" approaches, like Diamond and Saez (2011), suggest that the revenue-maximizing top tax rate is above 70%.

But this result is sensitive to the assumed responsiveness of taxpayers (Mathur et al., 2012), and more mid-range elasticities suggest a rate

of about 60%. Estimates from Neisser (2021) and Macnamara et al. (2024) suggest a rate near 50%, which is the

current top marginal tax

rate when considering federal, state, and local taxes.

But the "sufficient-statistic" approach misses the shape of the Laffer curve and ignores macroeconomic effects.

Meanwhile, macroeconomic models have used simplified tax functions that miss many behavioral responses and apply the top rate to incorrect tax bases — either too large or too small.

In Moore, Pecoraro, and Splinter (2026), we address these limitations by moving beyond the simplified approaches with a model that

better reflects important details of the U.S. tax code and captures a true tax base.

Our findings suggest the wrong question is being asked. It isn't just about the Laffer curve's peak, but its shape.

We find that the Laffer curve is quite flat. This means the exact revenue-maximizing rate is less important because

revenues changes are small around that rate. Flat Laffer curves also suggest less potential revenue gain from increasing the top tax rate.

● "Too broad" base assumes the top rate applies to all income, ignoring the fact that a large share of top income comes from

preferential capital gains and qualified dividends that are subject to lower tax rates.

● "Too narrow" base assumes the top rate applies only to wages, ignoring capital income taxed at ordinary rates, like interest

and passthrough business profits.

Instead, we use a detailed tax calculator as in Moore and Pecoraro (2023). This accounts for real tax brackets, the Alternative

Minimum Tax, surtaxes, and the complex web of deductions that actually determine what high-income households owe in taxes. This calculator is applied to the true tax base for ordinary income and calibrated using administrative tax data.

Another contribution of this paper is the analysis of tax interactions. Raising the federal individual income tax rate doesn't

happen in a vacuum. It interacts with payroll, corporate, excise, estate, state, and local taxes.

Adding realism in these ways affects the Laffer curve — the "peak" becomes a plateau.

When also accounting for state and local taxes, Laffer curves are even flatter than the figure below and raising the top federal income tax rate generates a negligible total government revenue gain. This is because behavioral responses to higher tax rates decrease not only the federal tax base, but also state and local tax bases.

A flat Laffer curve means choosing between tax progressivity or economic growth. We quantify that trade off. For example, raising the top rate to 70% might make the tax code look more "fair" on paper and slightly more progressive in practice (only one-fifth of the 1985-2015 increase in progressivity), but at the cost of GDP decreasing by 2%. In addition, total tax revenues likely decline.

Under current tax policy, simply ratcheting up the top marginal rate does not appear to raise significantly more tax revenue (relative to deficits). There are strong behavioral responses to tax-rate changes — from income shifting, avoidance, and reduced investment.

We introduce a realistic tax base into a realistic tax calculator and embed these into a macroeconomic model that captures these responses. This can lead to far different conclusions than standard frameworks.

Note that these are not policy recommendations. Also, the potential revenue gains from increasing the top rate are sensitive to other tax system details that are frequently changed (e.g., itemized and passthrough deductions) or rarely changed (e.g., the top-rate threshold and tax-base definitions).

With current tax policy, flat Laffer curves mean raising top tax rates presents a tradeoff between progressivity and growth, rather than an opportunity to raise substantially more revenue.

Read the full paper here (pdf).